How brands show old age and ageing

How can the stories told by the media about older adults impact our attitudes towards ageing?

In this guest blog, Dr. Dennis A. Olsen (Associate Professor of Advertising and Branding, London School of Film, Media and Design, University of West London) examines the different portrayals of old age in advertising.

A recent literature review by the Centre for Ageing Better titled 'Doddery but dear?' concluded that ageism, the systematic stereotyping of and discrimination against older people, was ‘still rife’ in the UK, including in its media. Considering the country’s increasingly ageing society, with the share of those aged 50 years or over now standing at almost 38% of the UK’s total population, this conclusion is a cause for concern.

In spite of their large and growing numbers, and the considerable spending power that many older people have, they are under-represented in advertising: just 29% of TV advertisements feature characters aged 50 years or older.

In industrialised societies like the UK, mass media communication plays a key role in the formation of people’s ideas about pretty much everything, including ideas of what it means to grow older. The saturation of media in our modern lives allows for ample opportunities for media messages to influence individuals and impart ideas and stereotypes—both positive and negative.

Some of the biggest drivers of media messages today are brands that want to tell their stories, especially via advertising. Advertising often comprises well-crafted short stories, featuring condensed characters within easy-to-follow storylines; and, as one of the most readily available forms of media content, advertising plays an important part in the formation of mental images and, at the same time, reflects the prevailing attitudes of society.

Studies have shown that storytelling, even fictional, has a persuasive effect on audiences. It contributes to people’s ability to learn new information, but also increases the receptiveness to false information. Consequently, (mis)information concerning ageing and old age in the media and advertising may influence all our perceptions of and behaviour toward older persons.

The question therefore arises, what stories are currently told by the media concerning older adults that might impact our attitudes towards ageing and old age? Advertising lends itself to this kind of investigation, as it offers a window into socio-cultural trends and influences audiences through what it shows, and what it does not.

What have we found?

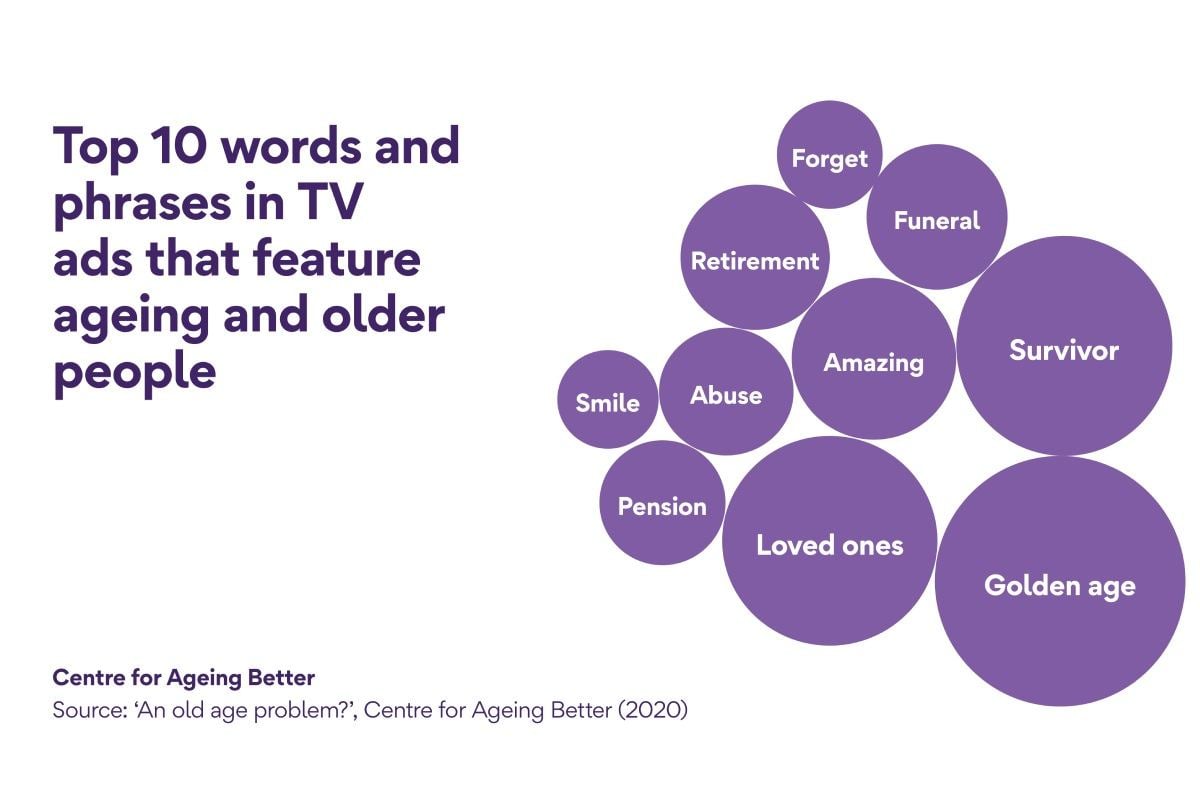

As part of an ongoing research project based at the University of West London, my team analysed more than 6,000 prime-time TV commercials to investigate the public’s perception of ageing and old age in the UK. All commercials aired on ITV, Channel 4 and Channel 5 during the investigation period were included in the analysis, resulting in a sample size of 6,228 adverts, featuring a total of 607 occurrences of characters over the age of 50 years.

We identified a total of eight common stories currently communicated in UK advertising centred around older persons. We present these here from most to least frequently aired:

Celebrity Endorsers are well-known older persons in the public eye, who throw their social status behind a product or a service. Their status as celebrity usually takes centre stage in the stories, whilst their age takes a backseat.

Golden Agers are young at heart and often presented as health-conscious, physically active and attractive.

Jane or Joe Public are depicted as typical members of society. They are often part of storylines that use a large range of characters in respect of age, sex and ethnicity, creating a reflection of a diverse society.

Perfect Grandparents are always featured in positive storylines, presenting happy and smiling older individuals who are in good health, laughing and enjoying the company of others – especially members of their family.

Comedic types are tied to humorous, even ridiculous and absurd situations. Narratives often tell jokes at the expense of the older protagonists involved.

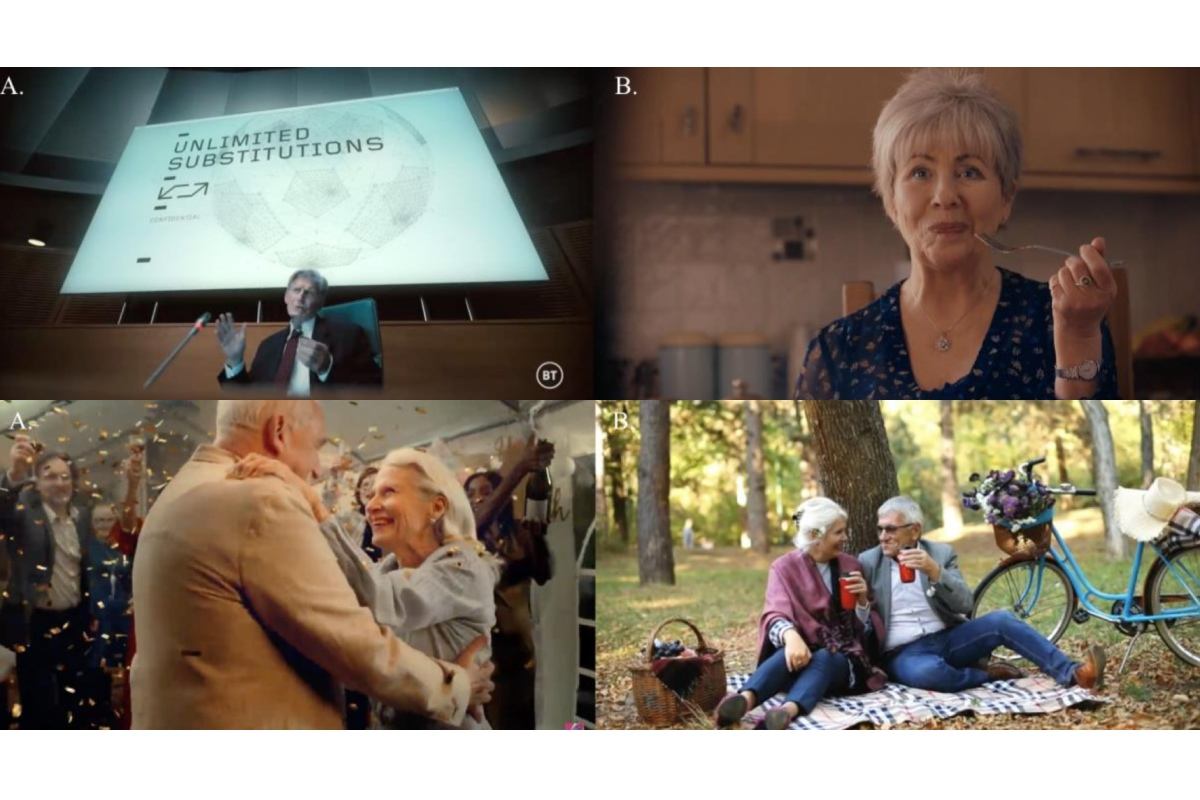

Happy Couples are in love, being physically affectionate and focused on each other. Their relationship and interaction with each other dominate the storyline and overwrite any other connotation.

Copers are protagonists with disabilities or stark physical, cognitive and social decline – conditions seen as things that go hand in hand with ageing.

Legacy or Mentors are similar to the Celebrity Endorser, but without the celebrity status attached. Their expertise comes from their professional and/or life experience, thus putting an emphasis on their age.

The storylines that we observed were multifaceted and largely positive in their connotation; yet, they were far from being a full reflection of real life of older persons in the UK.

Admittedly, there has been a trend towards representations of older persons in which they are depicted as vigorous, productive, attractive (and mostly well-off). While at first glance, this imagery of active and healthy ‘golden agers’ appears positive, it can be damaging in its own way too. This imagery has its origins in narratives of active and ‘successful ageing’, in which individuals are themselves primarily responsible for their own ageing trajectory with their own lifestyle choices governing how well or otherwise they navigate the ageing process. It does not consider that people’s experiences of ageing are largely determined by wider society, with policies and people’s environments impacting on their ability to age well.

Not achieving these idealised portrayals is to fail at ageing – and individuals themselves are to blame. Moreover, the Golden Agers narrative and imagery applies only to the younger old; the oldest old remain invisible. Due to the nature of advertising, a full reflection might be an unrealistic expectation in any case. Nevertheless, advertisers ought to be aware of the power they wield over public perception and attitudes with the storylines they select to present.

Public images can assign a specific place within society to individuals and create conditions that lead to the confirmation of that image – like a self-fulfilling prophecy. They can also cause compliant behaviour, by the mere fact that the group members concerned are aware of the existing public perception.

In ageing societies, such as in the UK, maintaining an open mind regarding the multiple potential social contributions of older persons is crucial not only to facilitate a more inclusive society, but also to remain competitive.

Looking at the frequency of current storylines, we would encourage advertisers to consider an increased use of two of the identified narratives in particular: For one, that of the Legacy or Mentor, thus assigning valued expertise rooted in an older person’s professional and/or life experience, detaching these achievements from any celebrity status; secondly, an increase of slice of life storylines, such as the Jane Joe Public, thus creating additional visibility and further normalising ageing and old age within the UK.

The views and opinions expressed in this guest blog are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect the policy or positions of the Centre for Ageing Better.

Image references

Stills were taken from commercials for the following brands:

Happy Couple: (A) Vanish, 2020; (B) Parkdean Resorts, 2020

Mentor or Legacy: (A) BT TV, 2020; (B) Princes, 2020