We need an integrated approach to updating our housing stock

Almost none of the UK’s homes are accessible for people with a disability, and many are poorly insulated and excessively cold.

Dr Richard Miller, founder of innovation consultancy Miller-Klein Associates Ltd, writes that to improve health outcomes, reduce fuel poverty and protect the environment, the UK needs a joined-up approach to upgrading housing stock that blends accessibility, energy efficiency and decarbonisation.

I grew up in the East End of London in the 1950s and 60s. Only one room in the house was heated in winter – the living room – and that was an open coal fire. The TV was next to the fire and the sofa was always angled across the room so that we could enjoy both. There was a stuffed fabric snake across the door to stop the freezing draft and shouts of 'Close the door!' erupted whenever anybody came in or went out.

In cold winters, I would wake to a tracery of frost on the inside of my bedroom window. Getting out of bed was something you had to steel yourself to do. I used to lay out my clothes the night before in the right order and the right way round for maximum speed of entry.

Things have changed. The house I grew up in has central heating in every room and fitted carpets everywhere. It’s the same in many homes, but the danger is that we assume these older, colder houses are no longer a problem. The truth is, there is still a lot to do.

Homes’ excess cold is a health crisis waiting to happen

Poor housing has a direct impact on health. Here’s the problem:

- Only about a third of England’s homes are reasonably energy efficient and almost none reach the highest standards required for future comfort.

- If you live in a colder, less efficient home, you are more likely to be in fuel poverty. About one-quarter of households in fuel poverty include someone over 60.

- Last year there were over 50,000 extra deaths in winter in the UK, much higher than recent years due the ‘Beast from the East’ cold snap and a less effective flu vaccine. Over 90% of the excess deaths were in people over 65.

- Poor health caused by poor housing costs the NHS at least £1.4 billion per year.

Relatively low-cost, minor adaptations, in combination with home repairs and retrofit, are a highly effective way of adapting our existing housing stock to meet the needs of older people.

Most of those suffering will be older, disabled or otherwise more vulnerable. Our housing stock fails older people in other ways. Only 7% of UK homes are ‘accessible’, with wide doorways and access ramps for wheelchair users or ground-floor bathrooms and grip rails to help people with reduced mobility. And almost half a million people (475,000) are living without the adaptations they need. Yet relatively low-cost, minor adaptations, in combination with home repairs and retrofit, are a highly effective way of adapting our existing housing stock to meet the needs of older people.

Improving the energy efficiency and accessibility of homes will help older people to live longer and more independent lives.

Room to improve: The role of home adaptations in improving later life

Wasted heat means wasted energy

There is another reason to improve energy efficiency. The UK has a legal obligation to cut carbon emissions by 80% by 2050. Every part of the economy must contribute, including the housing sector.

Domestic properties in the UK account for about 30% of total energy demand and 20% of carbon emissions. Because other sectors are even more difficult to decarbonise, we must reduce carbon emissions from domestic heating and cooling to zero.

That means we must minimise demand and decarbonise elsewhere. There are two problems:

- Over three-quarters of household energy demand is for space and water heating, mostly using gas. Without massive changes to the electricity grid, switching to electric heating using renewables would be impossible, as the winter heat demand is six times the winter electricity demand.

- The UK’s housing stock is old, and there’s low turnover. About 80% of the homes we will be occupying in 2050 already exist.

So, we can't rely solely on decarbonising the grid, and we can't rely on building new energy-efficient homes. We must improve the existing stock; retrofitting 26 million homes.

Retrofitting, improving and adapting our homes must be a priority

A recent report reviewed the need, the barriers to retrofit and what practical solutions exist. It said that to make efficient use of resources we should be targeting 'deep retrofit', a whole-house approach to design and implementation taking a property from its current state to net-zero energy demand in one step.

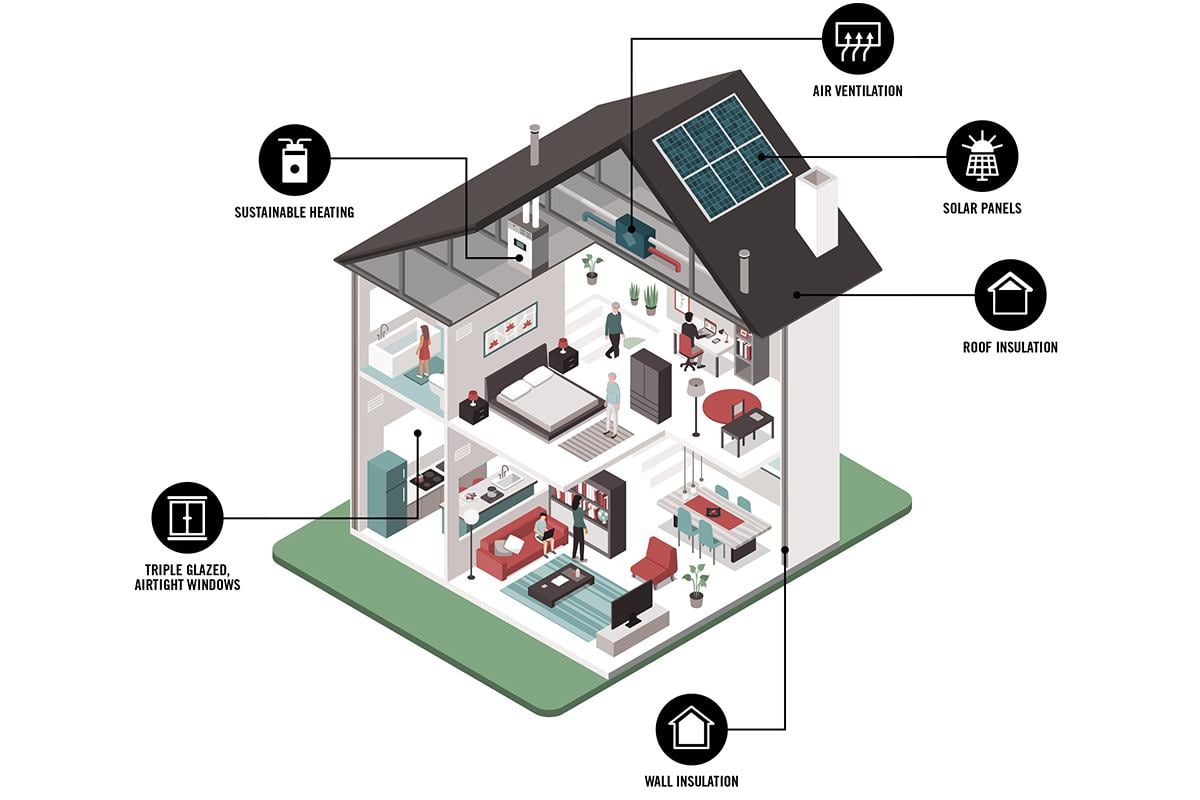

This sounds difficult and expensive, but recent pilot projects are showing that it is possible. One of the best approaches adds new insulated wall panels, windows and doors and a new insulated roof with integrated PV panels. What one architect described as 'throwing a duvet over the whole house'. Coupled with an air-source or ground-source heat-pump we can cut carbon emissions from space and hot water heating to zero.

This is a major retrofit, although with modern manufacturing techniques it can be done quickly and with minimum disruption.

But it raises the question; what else can we do at the same time? Why not carry out the adaptations and repairs required to make a home suitable for independent living by older people? Adaptations can improve quality of life and enable people to live safely at home for longer, and can reduce social care costs by up to £4,500 per person per year and cut GP visits by almost 50%.

Adapting for ageing: Good practice and innovation in home adaptations

We also need to adapt to ongoing climate change. A large part of the world’s population experienced a dramatic heatwave in 2018. Climate change has already doubled the risk of these extreme weather events. Excess heat kills as surely as excess cold, so we need to make our buildings resistant to overheating as well as energy efficient.

If we renovate our housing stock the right way, we can tackle multiple problems quickly and cost-effectively, adapting homes for an ageing population, reducing emissions and adapting to climate change.

If we deal with problems one at a time, it will be slow and expensive. An integrated approach is essential.