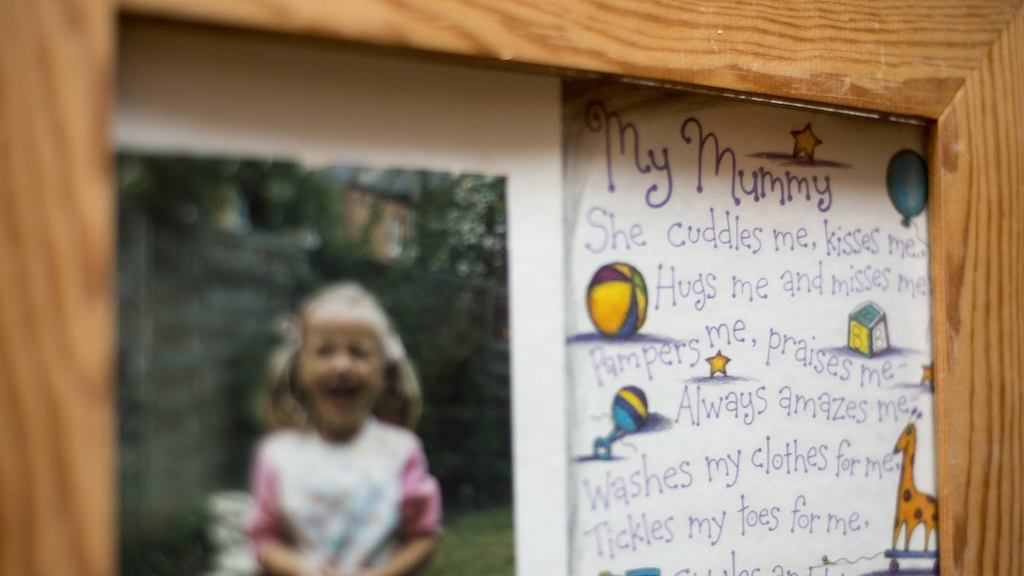

Our longer life expectancy is a seismic shift, but one that seems to have crept up on us too gradually, too quietly, and we find ourselves now with an urgent need to catch up. Nutrition, public health and medicine have given us this great gift, but our public policy, our private sector and our society haven’t properly shifted to embrace it. We need to do things differently and redesign our world to properly reflect our longer lives. Leading that charge should be an absolute priority for the next government. My daughter’s generation, and those beyond, won’t thank us if we continue to squander the opportunity these extra years should be giving us all.