We know people from minority ethnic communities are more likely to be living in poor-quality homes.

That is why the Centre for Ageing Better launched a project with the Race Equality Foundation earlier this year to ensure that support for home improvement was made more inclusive.

The project is looking at the current landscape of housing support and home improvements for people from minority ethnic backgrounds as well as the lived experiences of communities in trying to live in healthier, warmer, and safer homes.

As part of this project, a review of the existing research into what we know about the experiences of Black, Asian and minoritised ethnic communities in accessing home improvement services across England has been carried out.

This is what we learnt.

Structural and systemic racism and discrimination persists

Structural and systemic inequalities of racism and discrimination shape the housing experience of minoritised ethnic communities in England, particularly in terms of housing affordability, quality of homes and risk of homelessness.

Research in the 1980s identified substantial discrimination in social housing allocation, pointing to structural inequalities throughout services for Black, Asian and minoritised ethnic tenants. These patterns persist today, with lower home ownership rates and greater reliance on the private rented sector among some communities.

Importantly, even home ownership does not protect minoritised groups from housing insecurity. Wealth inequality leads to differences in housing quality, meaning that racial inequities persist even among Black, Asian and minoritised ethnic homeowners.

These inequities have contributed to long-standing housing insecurity for minoritised ethnic groups, with systemic discrimination playing a role in limiting their opportunities for affordable and suitable housing.

The need for home improvement support is higher than among non-marginalised groups

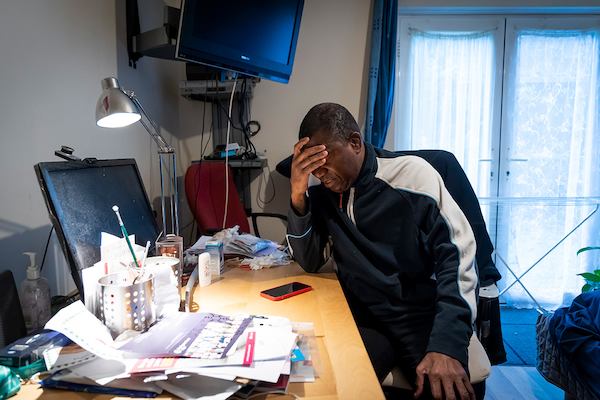

People from minority ethnic backgrounds are more likely than most to know about the impact of poor-quality housing from personal experience, with older people from minoritised ethnic backgrounds being over five times more likely to be living in housing deprivation than White British people. Their overrepresentation in the private rented sector, also makes them more likely to live in a home with a category 1 hazard, which have the potential to cause the most serious harm outcome that could lead to death or serious injury, and problems with damp in the home.

There is a rich historical evidence base exploring the links between race and housing looking at many aspects such as the experiences of different communities, how people interact with housing providers and how policies are developed and applied.

However, analysis published in 2022 found a decline in research focused on the housing experiences of minoritised communities over the past 20 years. This decline is concerning because it limits our understanding of ongoing inequalities and weakens the evidence base needed to shape fair and inclusive housing policies.

What does this mean for access to home improvement services?

There is very little in terms of evidence that points us to how interventions on the ground are working for different communities. There is a lack of evidence exploring housing improvement services experienced by minoritised ethnic communities in England.

Profiling data can significantly aid in the evaluation of service’s impact, allowing organisations to make data-driven decisions for improvement. This is especially important during a time when resources are scarce.

In a broader context, national understanding can influence policy decisions, fostering a more responsive and effective service landscape that can adapt swiftly to the evolving needs of the communities across the country.

Access roadblocks and service use

There has been no real exploration of the experiences of minoritised ethnic communities in accessing home improvement support and even less so on the drivers behind what leads people from these communities to make the changes they need or even ask for help in the first place.

There are key barriers that prevent people from accessing help including poverty, language, communication challenges and uncertainty of who and where to turn to for support.

Some reports have suggested that ‘cultural factors’ may also play a significant role in shaping access to home improvement services, particularly for people from Black, Asian, and minoritised ethnic backgrounds, with research identifying a lack of culturally inclusive services as a potential barrier for communities. This research found that African, Caribbean and South Asian respondents felt that their cultural and religious needs were not adequately addressed by staff.

Structural racism creates and reinforces ethnic inequalities in housing. Black, Asian and minoritised ethnic communities are more likely to live in socially and economically disadvantaged areas, experience higher levels of poverty and live in poorer-quality housing and have lower levels of awareness about available services due to a lack of targeted outreach. Consequently, the barriers to accessing home improvement services, such as financial constraints and lack of culturally appropriate support, are likely to be even more pronounced.

We know the role that home improvement services can make in boosting the nation’s health and wellbeing, but there is very little known about how minoritised ethnic communities' benefit, or do not benefit, from these services.

Moreover, there is a concerning lack of data on outcomes and experiences specific to these groups, highlighting a clear need for more inclusive and culturally sensitive approaches in policy and service design to address these disparities in housing improvement and housing adaptation services effectively.

Our effort to drive meaningful change

To fill this gap, the team at Race Equality Foundation have been speaking with key stakeholders, including experts by experience in understanding what needs to change.

The upcoming findings offer a valuable opportunity to shine a light on the experiences of minoritised ethnic communities and to understand more deeply the barriers they face in accessing fair, safe and suitable home improvement services.

Through listening to lived experiences and from those closest to the issues, the work aims to uncover not only the challenges but also the strengths and insights within these communities that can shape more inclusive and responsive approaches.

The recommendations that will follow this work are rooted in a commitment to equity and change. They will focus on practical ways to embed fairness into service design, improve trust and access, and ensure that the voices of historically underrepresented groups are no longer left out of decision-making.

By acting on these insights, there is real potential to reduce inequality and build services that truly work for everyone – starting with those who have too often been overlooked.