Guide: Developing a local ‘State of Ageing’ report

Our online guide will help you use data to understand how well people are ageing in your local area.

This guide aims to support local authorities, voluntary and community sector leaders and others who want to use data to drive change towards better later lives.

Contents

Designed as a whole document that proceeds in order, you can also navigate to the sections which are of most interest and can also stand alone. There are also tools/resources throughout designed to help you get familiar with ageing data and understand how to use it to support your work.

Introduction: why data is useful and what this guide offers

Understanding your local population, where and how well people are living and ageing, is fundamental to creating effective local ageing programmes and policies.

Using data in your work can help you better understand the needs of your population, design and deliver services more effectively, focus public and political attention on important issues for older people, and understand the impact your work is having.

Developing this understanding is also the first step on the journey to be coming an Age-friendly City and Community in the World Health Organisation’s Age-friendly programme cycle which recommends the production of a baseline report to understand your community’s starting point. However, this should not be a one-off process that you do at the beginning – you can continuously revisit your data as your plans develop and mature to ensure you are going in the right direction.

This guide builds on our national State of Ageing report, which brings together a wide range of data sources on ageing nationally, and our work on a local State of Ageing in Leeds.

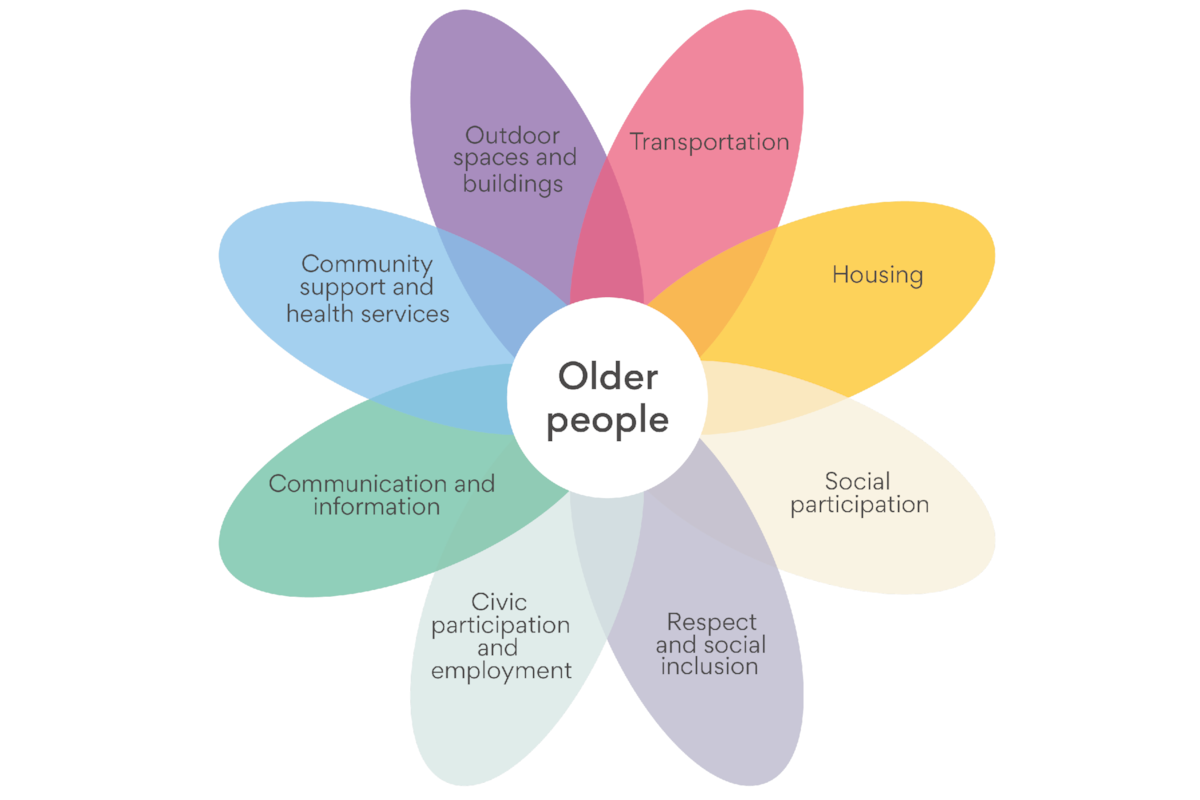

Introducing the age-friendly domains

To begin developing a data-led approach to ageing, it’s first useful to have a framework around which you can organise your data.

The World Health Organisation’s Age-friendly Cities and Communities framework is globally recognised, and well tested. It sets out eight domains of community life that local decision-makers, networks, and service providers need to consider in their ageing strategies. Imagine this framework as the ‘scaffolding’ of your data-led approach, enabling you to build up your understanding of the lives of local older people.

The outside environment and public buildings have a major impact on the mobility, independence and quality of life of people in later life. Characteristics of the built environment that contribute to being age-friendly include: access and safety, green spaces, walkable streets, outdoor seating and accessible buildings (with lifts, stairs with railings etc).

Transportation, including accessible and affordable public transport, is a key issue for people in later life. People’s ability to move about in the community impacts on participation in and access to services. Every aspect of transport infrastructure, equipment and service is integral to creating an Age-friendly Community.

Safe, good-quality homes can maintain or improve physical and mental health, wellbeing and social connections. It is vital to have housing and support that allow us to age comfortably and safely within the community of people’s choosing.

Social participation is strongly connected to good health and wellbeing throughout life. It is important to enable people to feel connected and have a sense of belonging, and maintain or establish supportive and caring relationships. Enabling accessibility, particularly for those with mobility issues, is also key.

An Age-friendly Community enables people of all backgrounds to actively participate and treats everyone with respect, regardless of age. Multigenerational activities are a great way for different generations to learn from one another.

Age-friendly Communities provide options for people in later life to continue to contribute to their communities. Those options can include paid employment or voluntary work and being engaged in the political process.

Staying connected with events and people and getting timely, practical information to meet personal needs is vital for active ageing. It is important to have relevant information that is accessible to those of us with varying capacities and resources.

Community support is strongly connected to good health and wellbeing throughout life, alongside accessible and affordable health care services. Both criteria are vital for maintaining health and independence as people age community grows too and health and social care funding will need to increase substantially.

For more insight into these domains, and some of the evidence and best practice behind them, check out Ageing Better’s page on the eight domains.

Selecting indicators

Indicators are key to a data-led approach to ageing, and this section will help you build an understanding of what they are, why you might use them, how to select and update them. It is designed to help you understand the considerations that go into using indicators, which you can then use flexibly as you start thinking about using data to inform your thinking on ageing.

Indicators are the things that we want to measure, to use as a headline, because they tell us (or indicate) something important about an issue that we care about and which can, when measured over time, give us an understanding of the progress being made. Indicators are most often quantitative, but we cannot understand their meaning without qualitative data.

Indicators exist at a range of different levels. We can measure ‘smaller’ things about projects that we run, like the number of participants in a service or the average time taken to assess a client’s needs (also known as operational performance indicators). We can also use indicators to understand the wider population and how the system is working, for example looking at the number of falls by older people in a local authority (also known as strategic indicators). This guide focuses on strategic indicators, because these will help you understand the conditions of ageing in your area. However, sometimes using strategic indicators is not possible, in which case more readily available operational performance indicators can be used as ‘proxies’ to help tell part of the story of change.

Indicators can:

- Help you understand what’s going on in your area and identify particular areas (neighbourhoods, groups of people, or topics) that require attention.

- Improve decision-making processes and practices, for example indicating where to target a particular service for older people.

- Enable the monitoring of progress, tracking change over time.

The process of selecting indicators is as important as the insight they provide. It is essential that this process is done in partnership with older people and other key stakeholders, across sectors and departments. While it might feel like more work, working collaboratively will help you choose more meaningful indicators and identify data sources that you didn’t realise were there. It can also begin to break down siloes, encouraging people to come together and focus their resources.

We have set out below some steps to help guide you through the process of understanding and selecting a meaningful set of indicators. Whatever your process, older people’s priorities and experiences should be central, and it is important to engage with a group of older people that reflects the diversity of your community.

The selection process can, broadly, follow three steps:

- Step 1: Build a working group. Your collaborative process should be led by a working group, bringing together different types of knowledge and skills. Who is available for this will depend on your resources, but would ideally bring in understanding of quantitative data, diverse older people’s experiences, the data that organisations in your area collect and need, and a rich understanding of your local area. It’s unlikely that one person could hold all of that expertise, so it is best to build a working group early on to bring together the necessary insights for the following steps. You might also want to look outside your organisation for people who have the skills needed to move the project forward; academic institutions, for example, can be useful partners.

- Step 2: Create a long list of indicators. If your area has a relevant strategy for ageing, you can develop a long list of indicators against the different aspects of it. If you are starting from scratch, we’d suggest using the eight domains of age-friendly communities around which to think through possible indicators. It might also be useful to consider your strategy against the eight domains, and consider if there is anything missing.

Example: You might have access to data on the uptake of concessionary travel passes. This doesn’t exist nationally, but might be collected locally and could be a useful indicator to add to your long list.

Start broad: this is the time to tap into the subject-area knowledge of your working group. It doesn‘t matter if you don‘t use a lot of this initial brainstorm; lots of indicators won‘t make it into your final set of KPIs but might spark useful conversations that clarify what you really care about in this process.

- Step 3: Assess the quality of the indicators in your long list. It is rare that an indicator will be completely perfect for you, and each needs to be understood in terms of what makes it useful and its limitations. Doing this will enable you to not only select good indicators, but interpret them well later. There are two sets of questions that can help you assess these indicators. The first set cover more technical aspects, and you might need support from data colleagues here for more information on the specific limitations/opportunities of the data sets that an indicator would rely on:

- Does the indicator conceptually link (or indicate) what you think it does? And is this what you need to know?

- Is the data that sits behind this indicator reliable?

The second set covers considerations more specific to your area and purpose. Some of these considerations you might want to apply to each indicator, and others to your set of indicators as a whole:

- How do these indicators speak to local priorities? Do they relate to upcoming strategies or policies that you want to influence?

- How does the data speak to the experiences of different groups (e.g. people from different ethnic backgrounds, with different sexualities, different health needs etc.) in your area? Which groups are missing from this data? (This may be another question for colleagues who are more familiar with the detail).

- Is the data relevant to your local area? For example, if you have a piece of regional level data, do you have good reason to think that your local area is either the same or very different to the region as a whole in respect of that indicator?

- As a group, do these indicators cover all the aspects of what you consider good ageing? Or are they clustered around particular domains? In which case, do you need to think more creatively about how to understand some of the other domains?

- What doesn’t the data tell us about the indicator in question that might be of interest? The ‘Dealing with data gaps’ section suggests options for further probing these gaps

Collaborate: the expertise of your colleagues can really help with these first questions. Those with specialist knowledge of ageing can help you think about the conceptual links, and data analyst colleagues can help you understand if data is reliable, e.g. considerations about whether the sample size is big enough, and what kind of more granular analysis (e.g. comparing gender, age groups, ethnic groups) is possible

Selecting indicators needs to be purpose-driven. Interrogate the purpose of each indicator with “why do we need to know this? What will we use this for? How will knowing this help us achieve a particular goal?” Otherwise you risk producing a lot of data, but not knowing what to do with it!

Example: Maybe you look at the average income of people over 50 in your area. It is quite high, which fits with your largely affluent area. But you also know that there are pockets of severe poverty, which are hidden by this averaging across the area. So perhaps you want to consider a measure of deprivation instead, at smaller geographical areas, to help identify where you need to be focusing support.

- Step 4: with this understanding, select a short list. This could just have one or two key headline indicators but, depending on the complexity of the domain and the extent of your scope for impacting it, you might want a few more. We recommend not having too many – there’s always a risk that an overload of data detracts from a clear and focused approach that you can bring stakeholders together around. However, if you do have a complex domain and a lot of useful data, you could break the domain into a few sub-domains which each have their own indicator set

How to shortlist: shortlisting should be a collaborative process; as ageing is an area which cuts across a lot of parts of a local authority, the developing agenda needs to be collectively owned. You could run a shortlisting workshop with the KPI working group, where you present the long list (some of them will also have been involved in that) and discuss the pros and cons of indicators. This discussion should be informed by the thinking that has gone into the long list, and their own expertise and understanding of the area and your goals. Some indicators might not be possible in your area, or might not reflect your understanding of how challenges should be addressed and thought about.

You don’t need to constantly update your indicators, but it’s important that they don’t become completely static; things change, and what is useful to measure does too. You might want to come back to a smaller core working group at relevant moments when you are refreshing local strategies, and consider whether this set of indicators is still the most relevant and useful.

You might also experience changes in your local area which mean it’s important to add a new indicator, to respond to a new situation. An indicator set is only as useful as it is useful to a particular context, so feel free to be flexible and practical when you update your indicators. Just be aware of why you are doing it, and what you are hoping to achieve.

The same goes for the data underpinning them. Some indicators will be based on datasets that get updated periodically (monthly, quarterly, or annually), and you’ll want to consider how often is useful for you to be monitoring these updates (do you really need to know monthly changes?). Other data sets might be a one-off, produced from a piece of analysis done by a government department or from the Census. As time passes, you’ll need to consider whether these are still relevant or have things changed considerably and it can no longer be relied upon to reflect current circumstances. This will need to be done on a case-by-case basis, bringing together insight into:

- Trends in the data itself i.e. does this figure usually change a lot month on month or year on year? Or is it stable for longer period of time? If so, it might not matter as much if it is a few years old.

- Your local area i.e. do you have reason to think that the local area has experienced some big changes which might mean that this data set has become out-dated?

Accessing quantitative data

There are two broad sources of quantitative data that you might want to use to build your understanding of ageing in your local area: national data sets that report on all local areas across England, and data sets that are produced within your local area.

Nationally produced data sets

Using quantitative data can feel like a step outside your comfort zone if you’re not familiar with it. While some people working on ageing will have support from data analysts in their organisation, others won’t. Some may have analysts available but aren’t sure what to ask them for.

To help you get started in delving deeper we have compiled a ‘Guide to data sources’, an overview of the nationally produced data that is publicly available on ageing at a local level for each of the eight age-friendly domains. This isn’t meant to be an exhaustive list (although we have tried to be thorough) but rather a starting point which sets out the broad landscape.

It is important to be cautious when interpreting data, and this overview is not intended to provide a blueprint to bypass the work needed to underpin that cautious approach. Instead, it is intended to give you a sense of what is out there, to help you inform your thinking and conversations with data analysts in your local authority if you have that support. We have limited this overview to sources that are available for areas across England. It might be that the data that you really want is not available across the whole country, but that it can be supplied locally, or that qualitative insights can be used to develop a richer local picture.

Many of the sources listed are direct links to spreadsheets where you can search for your area, while some require more user input. Stat-Xplore is the online repository of the data regularly published by the Department for Work and Pensions on welfare benefits, and requires more user input to shape and download the data. To help with this higher barrier to entry we have created a guide to help first-time users understand what Stat-Xplore can offer.

Finding local data with Census 2021

Headline figures for your local authority

We have brought together a few of the sources listed in ‘A guide to data sources’. You can view some headline figures on ageing by searching your local authority in the search bar below:

Type in your local authority in the search bar

Locally produced data sets

So far, we have focused on data that is available across England, but it’s very likely that your area also collects other useful data. It is crucial to engage with colleagues across your local authority to understand what data there is collected locally. You might do this informally through one-to-one discussions, or host a roundtable with colleagues where you discuss the domains of ageing well and brainstorm the data available within the council. This could include data on service use that departments collect, council surveys, or other kinds of knowledge that they have (quantitative or qualitative) about services and needs in the area.

In our work in Leeds, for example, locally produced data included: housing satisfaction; the prevalence of zero hours contracts in work; participation of people over 50 in adult education programmes; how residents travel and their perceptions of public transport in the area; rates of active travel; rates of social inclusion through local programmes and volunteering; and patterns of dementia within the city.

Example: Transport

There isn’t a lot of nationally collected data that tells you about older people and transport in local areas, and different parts of the country have vastly different transport patterns which makes national-level or even regional-level data quite unhelpful. However, everyone of State Pension Age in England and Wales is entitled to a concessionary travel pass and there will be data on the take-up of this from the issuing authority, which you can ask for and analyse to identify patterns within your older population of which groups are making use of this. Perhaps you collect demographic data in these applications already, or you might be able to identify the hyper-local areas where uptake is higher. You can then use your local knowledge of their demographic characteristics to inform some starting assumptions about who is accessing the pass, and which communities may need a more focussed approach to help them access it.

Example: Housing

The English Housing Survey (EHS) reports national and regional data; this isn’t necessarily very useful for understanding the housing of older people in your local authority because your housing stock may or may not have the same patterns and issues. However, the EHS can still be a useful starting point for thinking about housing in your area. If you look at the tables that the EHS produces through an ageing lens, you may get ideas for the kinds of questions that you could be asking of the housing team in your local authority who may already hold some of this knowledge.

You may also have some resource to produce new local data. Surveys are one method that you may be able to use, although they can quickly become expensive, and it might be more realistic to add some questions to any existing resident surveys. In 2019, Ageing Better produced our ‘Ageing Better Measures Framework’ that brings together high-quality, robust measures for understanding individual level outcomes around ageing. This provides guidance on the kinds of robust, validated questions that you could ask

Going beyond quantitative data

Often the things that you need to know to shape more effective policy and programmes, won’t come with a matching set of quantitative data, nationally or locally produced. Even if there is one, it can never tell you everything that you need to know to develop and monitor an effective approach around an issue. If you’ve explored the data sources linked in the section above, you might have noticed some of these gaps. This section of the guide introduces a range of approaches that you can use to supplement and enrich that data including: qualitative research; intersectionality; and guidance on interpreting data.

Gaps

For example, housing data largely comes from the English Housing Survey, a national survey which doesn’t publish figures for local areas. Similarly, a dataset reporting on your local authority as a whole won’t help you understand how things differ within the area. Some data sets let you compare between smaller areas, but they treat older people as one unified group rather than letting you understand how differences – like wealth, race/ethnicity, disability, gender, or sexuality – are shaping people’s experiences of ageing and their quality of later life.

Developing qualitative insights

It is important that when we talk about ‘data’ we don’t develop a tunnel-vision focus on numbers or quantitative data. What we are really interested in is building knowledge around ageing, and numbers are one tool for doing that. Qualitative data offers lots of other ways to produce new local insights, like running focus groups with older residents or doing interviews with service users. These could be focussed on particular issues which you already know are important locally – for example fuel poverty in a part of your borough – or they could be more exploratory, designed to uncover persistent issues facing older residents that are not already on your radar or develop an awareness of rapidly emerging issues.

Where quantitative data is not granular enough to represent different experiences in your local area, qualitative data offers another way to develop useful knowledge. Rather than trying to measure things, qualitative data gets behind the numbers and explores the nuance of people’s lives and experiences, and their understanding of ‘how’ and ‘why’ things are happening. As well as focus groups and interviews with residents, you might also want to think about case studies as another useful tool for exploring and presenting qualitative insights. These can be a variety of formats, including written case studies or short videos. Case studies let you dig down into something – a topic, a service/organisation, a person or neighbourhood – and explore it in depth.

Below are two examples produced by the Centre for Ageing Better on the challenges facing people in their 50s and 60s and experiences of ageism in job recruitment. This format, focussed on a few people and their stories, lets you explore ideas that can be hard to define, giving people the opportunity to articulate what they mean in their own lives and words.

You might also want to use case studies of your own work as a way of sharing good practice and learning with other areas working on ageing. Here is an example from the UK Network of Age-friendly Communities from a project in Newcastle on digital visibility.

Addressing intersectionality and inequalities

There isn’t one universal experience of ageing

There is not one universal experience of ageing. Experiences of older age differ between individuals but also, crucially, between different parts of the country and different parts of the population. We know, for example, that life expectancy is greater and health better among older people are in the south of England than the north (a pattern that mirrors the distribution of wealth and poverty across the country), and that older people from many Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic groups live with worse health than those from White ethnic groups, with variations also within those blunt groupings.

Such inequalities are not random but rather shaped by the effects of discrimination around race, gender, class, disability, and sexuality. Inequality is structural, it shapes how we are treated by society and the state: the kind of education we receive, the kinds of jobs we can get, the quality of our healthcare services our housing, and whether we will reach retirement with enough savings to live comfortably.

When we look at headline statistics, they often hide inequalities across the population

Turning to quantitative data can sometimes mean that we lose sight of these inequalities, because an overall trend or headline can mask a more complex picture. For example, an increase in life expectancy among your whole population can hide the unequal distribution of those extra years which might be accruing to wealthier groups while poorer groups see no change or even a decline in their life expectancy.

What can help: starting from local knowledge

To understand the limitations of a data set, you need to apply local knowledge to interpret it. This involves asking what are the different communities in your area, and what might be the structures of inequality that will shape their varied experiences of an aspect of later life? Similarly, are there ways in which thriving might look different in different communities which your data might also be masking?

Age is always playing out in complex combinations

It is also important to remember that to understand how inequalities are playing out it’s not just an experience of “ageing AND” another “category”. Rather, age (as a category) is interacting with multiple others at once to produce different inequalities and experiences. These intersections are complex meetings of discriminatory systems around gender, race and ethnicity, disability, and sexuality (among other things). For example, racism and gender creating unique experiences of systems of racism and sexism for Black women in later life which will be different to the experiences of their peers who are White women or Black men.

But most quantitative data does not let us look at this

Most current quantitative data doesn’t really help us think about these complex combinations, which were given the name “intersectionality” first in Black feminist legal theory. Looking back at the sources of publicly available local data that we highlighted above, you might have noticed that these nuances are rarely reflected. There are a couple of reasons for this:

- Small sample size of surveys (especially at local levels) often mean that there are not enough respondents to provide statistically robust estimates of smaller parts of the population

- This leads to an absence of minority groups in UK research, including Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic older people, disabled older people, and LGBTQ+ older people. For example, the UK’s largest survey of ageing, the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA), running since 2002, included less than 5% ethnic minority sampling at its most recent data release, in a country where 13% of people are from Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic survey of ageing, the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA), running since 2002, included less than 5% ethnic minority sampling at its most recent data release, in a country where 13% of people are from Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic backgrounds. A BMJ editorial has termed the exclusion of adequate Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic representation from population studies as a ‘form of institutional racism’.

Statistical robustness:

Quantitative data is often based on a sample of people – as it’s difficult to ask a question to an entire population, you ask a smaller group instead (a ‘sample’). A statistically robust sample is one that is large enough to be considered a reliable estimate for your population as a whole. The smaller your sample, the less robust it becomes. This means that samples of smaller groups within the whole often cannot be picked out (because the sample size becomes too small), thus hiding any differences.

What can help: thinking about differences within groups

Many datasets (even at a national level) only allow analysis of White compared to Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic groups taken as a single unit. Instead, a multi-ethnic approach (being specific when talking about ethnicity) allows you to understand more specific conditions impacting different groups while not denying that Minority Ethnic groups may well share some experiences of discrimination.

For example, if you are looking at differences in employment rates by both ethnicity and age you should attempt to compare the rates of different groups (e.g. White, Black Caribbean, South Asian or Pakistani etc.) rather than just White compared to Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic groups. You should be thinking about differences such as class, gender, disability, and sexuality between your ageing residents. Where you have a piece of quantitative data that gives you a headline but no more detail, you can use qualitative insights to develop an understanding of how different groups are experiencing that aspect of ageing.

This is far from a simple absence to address, made more complicated by a history in many communities – including Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic communities, also in White and multi-ethnic working-class communities – of high levels of government scrutiny, monitoring, and discrimination. With this history, it is vital that communities are actively involved in planning and interpreting data, that it is produced with them rather than about them.

What can help: reaching the ‘seldom heard’

When gathering any data locally (be that conducting a residents survey or running a focus group with a community group), it is easy to rely on the groups/parts of the communities with whom you are already have strong connections. However, it is important to push beyond these “usual suspects”.

Start by asking colleagues which community groups they can connect you with. Do these groups reflect the breadth of different experiences of ageing across your area? Are there other groups or less formal networks that you need to start building relationships with? This is particularly important as the people farthest from your usual circles might also be those experiencing the sharpest edge of inequalities in the area.

These are the parts of your community where you need to be focussing attention. The same goes for quantitative data. If you are commissioning a survey, for example, on older people and the costs of living crisis, consider which groups you know the least about, who gets hidden most in the national data, and who is likely to be most negatively impacted by inequalities in later life.

It’s important in all data collection to ensure that your methods don’t make it difficult for some parts of your population to take part. For example, you may need to consider translating surveys to reflect the languages in your area, or provide both an online and offline way of inputting into a discussion that you want to hold with residents to meet different access needs.

Interpreting your data

A data-led approach to ageing isn’t just about generating a number but using that number, putting it in context, to develop a richer understanding of where you are. People often hope that quantitative data will provide an answer, but it can be helpful to think of it instead as the start of many more questions.

By figuring these questions out, you reach useful knowledge. Sometimes the avenues of these questions won’t surprise you, and the answers that you’re finding will chime with what you know about your area already. At other times they might surprise you.

This is why it’s important to make interpretation a collaborative process, so that different understandings are applied to the data. Sometimes you’ll need advice from data analysts on the technicalities of a data set to inform discussions of what it is actually showing. It might also be useful to discuss your insights with other areas who are also thinking about ageing. It is vital to include older people in the interpretation process, to understand how they experience an issue and hear their insights about what kind of change they would value.

Ideally, we want to try and “triangulate” our data. This means drawing on a range of different sources and types of data – the numbers, the focus groups and case studies, the discussions with colleagues – to tell the full story and bring the numbers to life.

Triangulating data is both a quality assurance process – it helps us to ensure that the stories we are telling are grounded in reality – and a way to understand the key drivers of change.

For example, you download data from the Department of Work and Pensions which shows that 2,100 people in your area are receiving Pension Credit. This figure is accurate, but it doesn’t tell you much. You can calculate it as a proportion of state pension age residents, and find it’s 12%, but that still doesn’t tell you enough. You need to interpret it within your knowledge of poverty in the area, which you can build by bringing in the Income Deprivation Affecting Older People Index, and the knowledge of local service providers. You start to develop a sense of whether this 12% is good (everyone who is probably eligible is already receiving it) or bad (actually, a lot of probably eligible residents are currently missing out). But you still don’t know anything about the experience of those receiving pension credit – how did they know they could apply? Is the extra income enough, or are they still struggling?

You might also start to ask questions about how take-up varies across your area – are some communities or groups accessing it more than others, and if so why? Perhaps they have access to a hyper-local service which is signposting them, or there has been a campaign by a ward councillor. Perhaps many older people in one part of the community don’t have good English language skills and miss out on information about their entitlement. All these questions help you to build a better understanding of what is going on, and how you might be able to improve things.

Part of interpreting data is really understanding exactly what that data set is reporting. Quantitative data often comes with caveats around how it was collected, or who was included in the sample. Understanding these caveats helps your interpretation. If you receive some data from a department of your local authority, get in touch with the source and discuss your findings with them – they might add depth to your narrative or warn if you have misinterpreted!

If we want to understand whether older people can adequately heat their homes in winter, we might look at data on home insulation, fuel poverty and excess winter deaths. We might also try and collect qualitative data to build our understanding of the experience of living in a poorly insulated home, or the experience of someone who can’t afford to have their heating on due to the cost of energy. We might also want to speak to those maintaining local authority-owned homes, to understand how provision currently happens and where they feel it needs to be improved.

Benchmarking as a tool to help interpret data.

Benchmarking is where you compare a local indicator to different places or times. For example, you could compare women’s life expectancy in your local authority to the national or regional average. You could also benchmark against your own local authority now and track how life expectancy is changing over time.

Benchmarking offers a tool for interpreting data by giving you some extra information or context within which to understand what is happening in your area. However, to give you useful context, it’s crucial that you’re benchmarking against the right things.

Taking data back into your community

A data-led approach to ageing is one where you use quantitative and qualitative data to build a story of what it means to age in your area and inform your decision-making to improve it. While quantitative data can give you the scaffolding, the bare bones of the local context, the work of interpretation helps you fill in the details of this story. It’s important not to lose this richness of narrative when it comes to communicating what you have learned; this is the part of the process where you use this knowledge to continue engaging your stakeholders, build further buy-in, and inform the public and policy conversations around later life.

Here is an example of a video produced by Ageing Better to develop the narrative around our State of Ageing report, focused on the voices of older people.

It is crucial that your data-led approach is something that you can take out into the world and share with residents and colleagues across your local area. This is part of refining the work, refining your understanding of local ageing and using data to energise local networks and inform local decision-making and planning.

You can read about exactly how we approached this in Leeds, and the opportunities it opened up, our evidence cards which you can update to share your findings, and our free image library with over 1,500 positive and realistic images of older people to use in your reports by clicking the links below.

Create your own infographics

Sign up to receive the latest news, research, policy updates and events about ageing.

SubscribeContact our team for more information

Contact us