Communities | The State of Ageing 2022

Despite the importance of staying connected to our community, inequalities are shaping people's quality of life and access to support.

The State of Ageing 2022 is an online report with multiple chapters. Below, you can get further detail by clicking on the 'Find out more' buttons and you can hover over graphs to access the data. You can also download the Summary.

Key points

- Our social connections are vital for our wellbeing. In the first year of the pandemic, over 50s with better connections to their local community reported higher overall quality of life than their less well-connected peers.

- The initial boost in connection to their communities experienced by many in their fifties and sixties at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic had waned by the second lockdown in November 2020.

- But the increased community spirit brought about by the pandemic has not been experienced equally. People belonging to BAME communities in their fifties and sixties were twice as likely to report that the pandemic has had a negative effect on community relations than people with White backgrounds.

- Inequality shapes people’s access to community support. Men, people from BAME backgrounds, and those struggling financially were less likely than others to know of local voluntary groups that offer support, and many poorer and disabled people didn’t benefit from better connections until later in the pandemic, if at all.

- A decline in formal volunteering in the first year of the pandemic, especially among people over 65, was matched by an increase in informal helping out in communities – although this also waned to some extent by the second lockdown.

- There has been a dramatic increase in internet use by people aged over 75, rising 7 percentage points in 2020. But, although internet use is still increasing among 55-74 year olds, the growth is slowing and there are still over 3.1 million people aged 55 and over who have never used the internet. A quarter of people aged 65 and over with internet access lack the skills to use it independently.

- Cuts in funding to community services – for example, cuts of almost 50% in a decade for libraries and public toilets – and the COVID-19 pandemic have affected people’s access to community services and spaces, reducing their ability to maintain social connections locally.

What needs to happen

The creation of communities that enable older people to be active, participate in and shape the places they live in by:

- Central government providing sufficient funding, powers and accountability for local and regional government to take an age-inclusive approach to promoting the general well-being of a community.

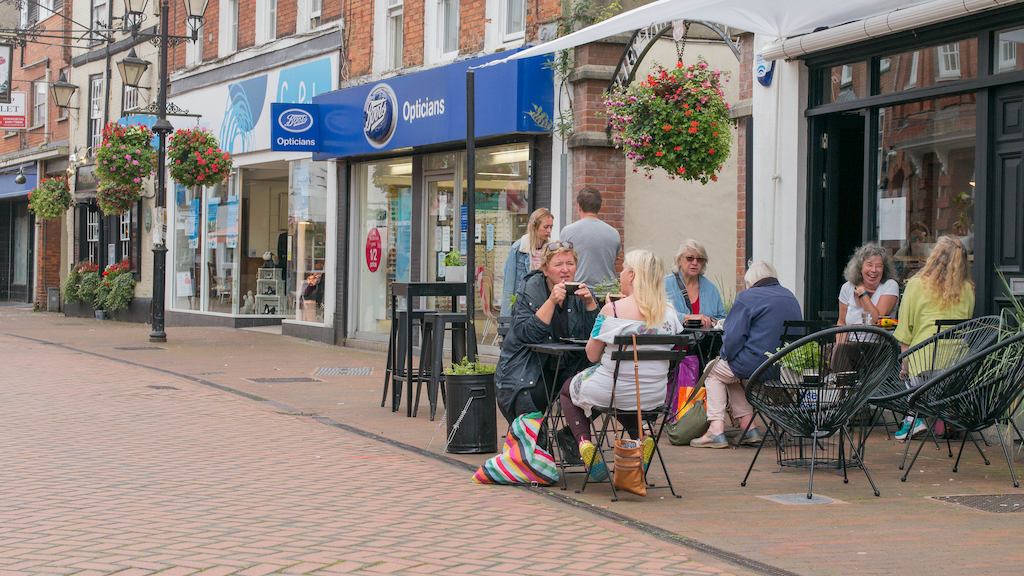

- Central and local government investing in communal spaces, high streets, public transport and making communities accessible and walkable, all of which will enable people to participate in and contribute to their communities as they grow older.

- Central and local government supporting digital inclusion by helping people to improve their digital skills and ability to get online, while providing offline alternatives.

Recognition of and support for the role that community services and the voluntary sector play in health and wellbeing by:

- Central and local government and other funders providing multi-year funding to community-based organisations that during the pandemic showed the vital role they play in helping older people at greatest risk of social exclusion.

- Voluntary and community organisations re-engaging with older volunteers post pandemic and enabling people to get involved in an ‘age-friendly’, flexible and inclusive way to increase the diversity of volunteers.

1. Community connection

Older people feel the greatest sense of belonging to their neighbourhood, but the gap with younger people is closing

What does the chart show?

- One measure for how connected to our communities we feel, is whether or not we feel we ‘belong’. Generally, the older we are, the more likely we are to say this.

- However, the gap between older and younger people is narrowing, as more younger people report ‘belonging’ to their neighbourhood. The gap in sense of belonging between people aged 16-24 and 50–64 halved between 2013/14 and 2020/21 (from 22 to 11 percentage points).

- In the last year, all age groups have shown an increase in the proportion who felt that they belonged to their neighbourhood. This increase was greatest among people aged 25-34.

We also know that:

- This reported ‘belonging’ varies across the country and is higher in rural than urban areas.

- Our social connections are important for our wellbeing. In the first year of the pandemic, people aged 50 and over with more community connections reported higher overall quality of life than their less well-connected peers.

- While White people’s sense of belonging increased, the sense of belonging in several minority ethnic groups decreased slightly in the first year of the pandemic (between 2019/20 and 2020/21).

People who might need most support took longest to improve community connections during the pandemic

What does the chart show?

- Last year, we reported that more 50-69 year olds who were ‘living comfortably’ knew more people ‘to count on’ in July 2020 than before the pandemic, compared with those who were struggling financially. Three-quarters of people who were well off (76%) knew more people they could count on to help out, compared with less than half of those struggling financially (46%).

- But between July and November 2020, almost twice as many people who were struggling financially (40%) agreed more that they knew people to help out compared with those comfortably off (22%). This suggests improved community connectivity in a crisis was delayed for people who were struggling financially.

We also know that:

- Similarly, there was a delay in increased sense of belonging for people with long-term health conditions. Only a third of people aged 50-69 with long-term health conditions that affected their lives a lot felt a greater sense of belonging to their neighbourhood in July 2020 than before the pandemic, compared with half of those without health conditions. Looking at changes among individuals between July and November 2020, 31% of people aged 50-69 whose long-term conditions and illnesses affect their day-to-day activities a lot reported an increased belonging in November compared with July– which is a higher proportion compared with just 19% of people in the same age group who had no long-term condition.

- While improved community connections were fairly widespread in the pandemic, overall this suggests that people who might benefit the most from better connections were the last to experience them.

The gender support gap is widest in our fifties and sixties

What does the chart show?

- More than seven in ten men and women in all age groups have people there for them if they need help, except for men aged 50-64 where the figure is slightly lower (67%).

- For women, knowing someone to count on for support increases up to the age of 74, but men are behind women at all ages from 25 onwards with an 11-percentage-point gap between men and women aged 50-64 (78% vs 67%).

- From age 65 upwards, the gap between women and men starts to close, although in later life women are still more likely to have someone to count on.

We also know that:

- A greater proportion of people of all ages had someone to rely on last year, after several years during which this had declined.

- Compared with last year, the gap between men and women has closed, particularly for those under 35 and over 65. Men in their fifties and sixties are more likely to report poor relationships with family and friends than women, and nearly one in ten (9%) of men in this age group say that they have no friends.

- With increasing numbers of men in their fifties and sixties living alone there is a growing need for inclusive community support for men as they age.

Awareness of support available from voluntary groups is lowest among people who might need it most

What does the chart show?

- Awareness of voluntary groups was lower for people from BAME backgrounds, with 45% aware of local groups compared with 55% of White people.

- It was also lower for men (49% aware vs 60% of women) and for people finding it difficult to get by financially (46% aware vs 59% of people living comfortably). There were no differences according to people’s levels of health or disability.

We also know that:

- Awareness of support from voluntary groups varies by region, from 28% of people in their fifties and sixties not knowing where to get support in the West Midlands to only 16% being unaware in the South East.

- In all areas except the South East the percentage of people in their fifties and sixties who were unaware of local voluntary groups that provided support increased between July and November 2020 by varying amounts.

This data shows how different phases of the pandemic have impacted community connections for older people. Early in the pandemic, in the first six months of 2020, communities rallied round in the crisis and there was a general increase in many people’s feelings of belonging to their local area. This was especially felt by people aged 60 and over, even though many were shielding in their homes, and older people generally continued to report stronger community connections than younger people as seen previously. Neighbours helped each other out and in many areas there were local community crisis responses to support those in immediate need, and more people of all ages knew someone to rely on in a crisis.

However, this boost in community connections was not experienced equally by everyone. While, by November 2020, the proportion of people aged 50-69 who reported that the pandemic had had a positive effect on their community relationships was about the same as the proportion who reported that it had had a negative effect (23%), negative effects were more likely to be reported by men (25%), people in BAME communities (42%), people finding it difficult financially (40%), and those with long-term health conditions that significantly affect their lives (42%).

It is unsurprising that many older members of BAME communities did not feel increased connection to their local neighbourhoods in the first year of the pandemic. Health inequalities in BAME communities (see more on this in our health chapter) gave rise to greater requirements to shield as well as increased caring responsibilities, causing many to become more disconnected. The loss of social spaces that are particularly important for older BAME community members to stay socially and culturally connected was felt acutely in these communities and will also have had a significant impact. So, although people in their fifties and sixties from BAME backgrounds were as likely as White people to know people to say hello to in their communities, it is clear that having casual connections with neighbours is not enough, on its own, to create a sense of belonging to an area. However, we do need to expand data collection so that we can better understand the different experiences of people in BAME and White communities as they age.

As the pandemic continued into 2020 the initial surge in community connection seems to have waned, with fewer people helping out and lower awareness of groups to go to for support. But this wasn’t the case for everyone. Last year – early in the pandemic – we reported that people in their fifties and sixties with long-term health conditions or illnesses that greatly impacted their lives were less likely to feel connected to their neighbourhood. By November, this group of people were more likely than those unaffected by health conditions to report an increase in belonging. The same was true for other marginalised people in communities: those who were struggling financially tended to become more connected to communities later in 2020, and especially knew more people they could count on for help. Thus, those who were most in need took longest to experience that boost in belonging that others felt early in the pandemic. This delay reflects the challenges that people who face structural inequality, through for example poverty or discrimination, can face in accessing community support.

It is essential to help people maintain their sense of belonging in their local communities as COVID-19 restrictions change, and to recognise that some individuals and communities have felt the impact harder than others. We may be expected to ‘learn to live’ with COVID-19 but many people aged 50 and over, especially those labelled ‘vulnerable’ to COVID-19 infection, have lost confidence in accessing the places and activities they used to enjoy in communities.

Unless people in their fifties and sixties who are at the greatest risk of missing out are considered when planning communities and designing local services, inequalities in older age will deepen and become more entrenched. There are particular risks in crisis situations where public sector responses tend to become more centralised and top down. The Age-friendly Communities model provides an approach to community-led organising that increases resilience, should there be a virus resurgence or other crisis. At a strategic level, English devolution provides new opportunities to work with Mayoral and Combined Authorities in bringing together local authorities, public, private and voluntary sector to improve the lives of people aged 50 and over in local communities.

2. Volunteering and helping out

Informal volunteering increased in the pandemic, while formal volunteering declined

What does the chart show?

- In 2020, there was a drop in regular formal volunteering and an increase in informal volunteering for all age groups, except for people aged 65 and over, for whom levels of informal volunteering remained almost the same as the previous year.

- The largest increase in regular informal volunteering was seen among people aged 35-49 (7.7 percentage points), with an increase of 6.7 percentage points among those aged 50-64.

We also know that:

- While older people were more likely to stop formal volunteering, they were as likely to take up new volunteering opportunities as younger people.

- Although the largest drop in regular formal volunteering was among people aged 65-74 (8.4 percentage points), this age group is still the most likely to volunteer, with 22% of people regularly volunteering.

- People aged 50-64 had the second largest percentage of formal volunteers, with 19% regularly volunteering.

- The increase in informal volunteering was mostly among 25-65 year olds, although with 37% of people aged 65-74 regularly providing support, this age group still has the highest rate of informal volunteering.

People who live in less deprived areas are more likely to volunteer – although the gap is much smaller for informal volunteering

What does the chart show?

- Among those aged 50 and over, there is a big difference in the proportion of people who formally volunteer, depending on where they live, with those in the least deprived areas almost three times as likely to formally volunteer (28%) as those in the most deprived areas (10%).

- The gap is much smaller for informal volunteering, with those in the least deprived areas about a third more likely to formally volunteer (39%) as those in the most deprived areas (30%).

We also know that:

- In all but the most deprived areas overall rates of volunteering (formally or informally) increase with age, from around 20-25 up to 74 years, but in the most deprived areas there is no increase from young adulthood.

Helping out in neighbourhoods declined following the crisis response early in the pandemic

What does the chart show?

- In both July and November 2020, rates of helping out others increased with age. In July, 40% of people aged 70 and over helped out compared with 34% of those under 50, and in November 33% of people aged 70 and over helped out, compared with 25% of under 50s.

- After an initial community response early in the pandemic, levels of helping out in communities had decreased in all age groups by November 2020. The smallest drop – from 37% to 31% – was seen in the 50-69 age group.

It is not surprising, given that many voluntary organisations had to suspend face-to-face services at the start of the pandemic, that formal volunteering across all ages decreased in the year 2020/21. It is equally unsurprising, with government direction to shield at home for many, that the largest drops in formal volunteering occurred among older age groups. However, people aged 50 and over were as likely as younger people to take up new formal volunteering opportunities. As a result, people aged 50 and over were still more likely to volunteer overall, except in the most deprived communities. Disadvantage in these communities accumulates with age, affecting, for example, health and finances, which increases the barriers to volunteering.

Other patterns of pre-pandemic volunteering continued, with volunteers being mainly healthier, wealthier and White. However, it does seem that there was less of a drop in volunteering in some BAME communities compared with White communities, and that a higher proportion of people aged under 50 from BAME backgrounds than White backgrounds volunteered. This perhaps reflects the mobilisation of people in BAME communities, which faced disproportionate challenges during the pandemic. Also, the volunteering rate gap between people living in more and less deprived communities is much smaller for informal than formal volunteering.

Community contributions are broader than formal volunteering, and include neighbourliness and informal organising. Early in the pandemic there was a groundswell of informal support in local communities, with most people both giving and receiving informal support in the first lockdown. By the second lockdown in November 2020, fewer people were providing informal support and this appears to have become more targeted towards the people who might need it most.

Contributing to our communities is important in the lives of many older people, providing sense of purpose and social connections and increased self-esteem. The loss of older people’s contributions impacts on community groups, communities and the individuals themselves. Steps need to be taken to re-engage the over 50s in their communities through inclusive approaches. The importance of informal helping out should be valued, while also increasing the diversity of volunteers by removing barriers to volunteering.

3. Digital connections

2020 saw a dramatic rise in internet use among the over 75s

What does the chart show?

- Internet use among those aged 45 and over has steadily increased over the last eight years. By 2020, 95% of people aged 55-65 used the internet, which was higher than the rate of 92% for all adults.

- Rates of internet use continue to decrease with age: people aged 75 and over are still much less likely to use the internet (54% compared with 92% of all adults), while those aged 65-74 also lag behind (at 86%).

- As internet usage heads towards 100% in most age groups, the rate of increase each year has declined for all age groups, except for those aged 75 and over.

- There was an unprecedented increase of over 7 percentage points in people aged 75 and over using the internet in 2020, undoubtedly driven by the pandemic restricting other ways of staying in touch and accessing services.

- In the 65-74 age group, the year-on-year increase in internet usage dropped to 2.3 percentage points from over 3 points previously, despite the pandemic and the fact that this age group lags behind the average internet use.

Digital exclusion in mid-life is twice as high among disabled people as their peers

What does the chart show?

- Disabled people aged 55-64 are over three times as likely as their non-disabled peers to have never used the internet (7.4% vs 2.2%). For disabled people aged 65-74, they are almost twice as likely to have never used it (16.3% vs 8.7%).

We also know that:

- Disabled people aged 55-64 are at least five years behind their non-disabled peers in internet uptake: 7.4% of disabled 55-64 year olds had never used the internet in 2020, compared with 6.8% of non-disabled people in this age group in 2015.

Over 3 million people aged 55 and over have never been online

What does the chart show?

- Over 3.1 million people aged 55 and over in the UK have never used the internet.

- While the majority of these people are aged 75 and over, there are still more than 1 million people aged 55-75 who have never used the internet.

The pandemic has prompted an unprecedented increase in the number of internet users aged 75 and over – almost half a million (461,000) in 2020. Although age still remains the biggest predictor of whether someone is online, the numbers of older internet users will increase without any intervention as confident younger users age. However, there are risks that some people get left behind, and simply accessing the internet doesn’t necessarily mean you have the skills to make the most of it. While eight in ten people aged 65 and over now have internet access, only six in ten have the skills to be able to access the internet independently.

Being online has the potential to increase inclusion of disabled people by connecting them to family and friends, enabling access to services, and reducing barriers to participation in public conversations. Yet many disabled people aged 50 and over don’t have the necessary digital technology or skills, or may be excluded from inaccessible online services, and so are over-represented in those not online. Individuals with hearing or visual impairments have the lowest level of essential digital skills, and people aged 65 and over are almost twice as likely to have a visual impairment than those under the age of 65.

Education level is also an important factor: only one in three people of all ages with no formal qualifications have the essential digital skills for life, compared with nine in ten of those with a degree.

Working from home in the pandemic has been a major reason for improved digital skills for those in office-based employment, bringing benefits in other areas of their lives, but many have not had this opportunity. People who are digitally connected not only earn more on average, but are also in a position to save more on bills (more than £200 per year on average) compared with the least engaged. So, digital proficiency becomes ever more urgent given projected cost-of-living increases and energy price hikes.

As more older people get online, policies and initiatives to support digital inclusion of older people need to be targeted at those offline who are now likely to face multiple barriers. While people in their sixties mainly prefer to learn new digital skills from family and friends, many may not have access to this ongoing support, or may need more specialist help.

4. Social and physical infrastructure

Local authority spending on key community services fell sharply in the decade between 2010/11 and 2019/20

What does the chart show?

- Since 2010/11, local authority spending has fallen sharply across a wide range of community services, with spending on libraries and public toilets falling by 47% and 48%, respectively, and that on community development by 58%.

We also know that:

- Community services continue to be important throughout life: around a third of people over 25 used a library in 2019/20, and this didn’t vary much through adulthood.

- Access to well-maintained public space with good facilities, including public toilets, is vital for people to continue using social infrastructure as they age.

- Overall, reductions in funding from central government have hit more deprived local authorities harder than wealthier ones. This is partly because deprived local authorities are more reliant on money from central government, while richer local authorities can rely on more income from fees and local tax revenue.

- The situation worsened for many local authorities in 2020/21 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, although we don’t have the full data yet. Local authorities both lost income due to the pandemic and had to divert funding from other services to cover the increased need in areas such as public health and support for homeless people.

- In contrast, the number of voluntary organisations has remained fairly stable, with a slight decrease in the number of the smallest organisations. And voluntary sector employment grew by 20% in the decade to 2020, a higher rate than in the public or private sectors.

People in their fifties and sixties take more car journeys than other age groups

What does the chart show?

- People in their fifties and sixties on average are the highest car users, and make many more trips by car than other mode of transport.

We also know that:

- As might be expected, in 2020 during the pandemic the average number of trips by all modes of transport, except bikes, fell across all age groups.

- People aged 70 and over saw the biggest reduction in bus travel, in line with government directives for older people to avoid public transport.

- People in their fifties and sixties averaged around five fewer trips a week than before the pandemic. Some of these will be accounted for by working from home, but even people aged 70 and over averaged four fewer trips per week.

Community assets and services provided by local authorities are vital to provide the social and physical infrastructure that helps people maintain social connections as they age. People’s social connections and use of public spaces, such as parks, are linked to their wellbeing and therefore can play a preventative role in reducing pressure on statutory services such as health and social care.

As funding for local authorities from central government has declined, with a real-terms cut of 37% in the decade to 2019/20, local authorities have needed to make difficult decisions about spending. They must try to maintain levels of provision for statutory services, so discretionary services – such as community services – often bear the brunt of spending cuts. But, although services have been cut back, the scale of the decline in such activities may not be as great as the funding cuts. Local councils are trying to maintain similar levels of service for less money by, for example, moving them into the voluntary sector, or changing the way they are run. The figures we have available are for the year before the COVID-19 pandemic, but it is predicted that the situation will have worsened in 2020/21 as local councils lost earned income from services and had to meet increased demand – for example, in public health services.

In contrast, there has been continued growth in employment in the voluntary sector, although the number of very small organisations declined slightly. In 2020, there was an increased movement to address structural racism within the voluntary and community sector and its funders, in the face of long-term underfunding of BAME-led community groups and catalysed by the Black Lives Matter movement. People from BAME backgrounds continue to experience inequality in public spaces. Our research has highlighted that Black and Asian people in their fifties and sixties were many more times likely than White people to avoid places in communities for fear of physical attack. While community-led services and activities are important for all, they play a particular role in maintaining social connections for people belonging to marginalised communities of identity.

The pandemic has had a huge impact on people’s access to places, spaces and people in our communities, as shown by the drop in the number of journeys that people made in 2020. People living in rural areas have been particularly affected by cuts to already infrequent public transport services. Access to regular, accessible, affordable and safe public transport becomes more important as we age, as does the quality of the public realm in our immediate locality.

Restrictions in travel during the pandemic have provided an insight for many into the importance of our local neighbourhoods. Looking forward, the three imperatives we face – the climate crisis, an ageing society and addressing inequality – mean that we will need to think differently about physical and social infrastructure. We will need to rethink our use of private transport, currently high among people in their fifties and sixties, and pay greater attention to the role that shared spaces and services in people’s immediate locality can play in improving quality of life as we age. Central and local government, and civil society, need to take action now to ensure that the benefits of spending time in public spaces, and getting out and about in our communities can be enjoyed by everyone.