Reform needed to stop unpaid carers paying the price for their vital role

Unpaid carers’ reward for providing a secondary National Health Service is to be left substantially worse-off in employment and in retirement.

Our Senior Evidence Manager, Dr Aideen Young, argues that unpaid carers need greater help to balance their caring duties with work if their propping up of the health of the nation is to be sustained.

Unpaid carers – those who look after others who are disabled, frail, or ill, whether their own family members or others – play a vital role in our society. By enabling their family members to stay at home, unpaid carers remove the need for formal care services.

As our latest State of Ageing 2023/24 report details, almost five million people aged 16 and older provide unpaid care in England, and almost a third of them do so full-time (50 or more hours a week).

But with many people not recognising what they do as unpaid care, the numbers could be even higher. Carers UK has suggested that the number of unpaid carers could be as high as 10.6 million. Importantly, people who are already disadvantaged – namely people living in areas of deprivation, people with minority ethnic backgrounds and Disabled people – are disproportionately represented among unpaid carers.

With so many people being cared for outside of formal services, the savings to the NHS and social care are enormous. The value of unpaid care has been estimated at £162 billion per year in England and Wales, making it larger than the entire NHS budget in England (£156 billion for 2020-21).

And with forecasts projecting 2.5 million more people living with major illness by 2040, it seems inevitable that the number of unpaid carers will only increase. Carers UK have estimated that by 2037, the number of carers across the UK could increase to 9 million. It is not an exaggeration to say that without our unpaid carers, our health and social system would collapse.

Who are the nation’s carers?

The implications of caring for work and finances

Caring for someone else, can have a huge impact on the carer’s own ability to work. Those who provide the highest levels of care are often unable to work at all, and many of those with lower levels of caring responsibilities will only be able to work part-time, and even then will require some degree of flexibility.

In fact, caring responsibilities are one of the principal reasons that people have left work or are thinking about leaving work. Approximately four in ten carers under retirement age are not working as much as they would like to because of their caring role.

The experience of older carers “Something’s got to give”, but obviously it’s not going to be my daughter. So, I had to pack in [abandon] work for that reason.

And not being able to work, or to work as much as one would like to, inevitably has a knock-on effect on the financial security of unpaid carers.

Even though unpaid carers are eligible for benefits of £81.90 a week provided they care for someone at least 35 hours a week (subject to certain eligibility criteria), balancing work and care results in fragmented work histories resulting in a huge impact on income and pension contributions during a working life.

As a result, carers are one of several groups said to be under-pensioned, with an average income from private and workplace pensions that is 28% lower than the population average.

In addition, there can be a significant financial cost associated with caring, with carers often having to pay for services and equipment out of their own pockets.

Unsurprisingly then, almost a quarter of pension-age carers are in relative poverty (24% of women and 23% of men), compared with 21% of pension-age women and 17% of pension-age men who are not carers.

Almost a third (30%) of carers are struggling to make ends meet, and one in three have had to cut back on essentials like food and heating. Two thirds of carers are extremely worried about managing their monthly costs.

Yet only a small percentage of carers approach their local authority for help. In 2021, only 8% of carers in England did so, and of those, only one in four received direct support.

Financial difficulties have a significant impact on carers’ physical and mental health. Isolation associated with caring responsibilities can also lead to loneliness and poor quality of life. Whether because of financial difficulties or isolation, 1.3 million older unpaid carers aged 65 and over (61% of this group) have felt unhappy or depressed.

In addition, four in ten female carers aged 55 to 64 have reported general stress and tiredness as a result of caring while more than a quarter have reported disturbed sleep.

With ill-health another of the main reasons that people of all ages fall out of the workforce, it is clear that the adverse effects of caring on the physical and mental health of carers not only increases their own need for treatment and support, but may further limit their ability to participate in the workforce.

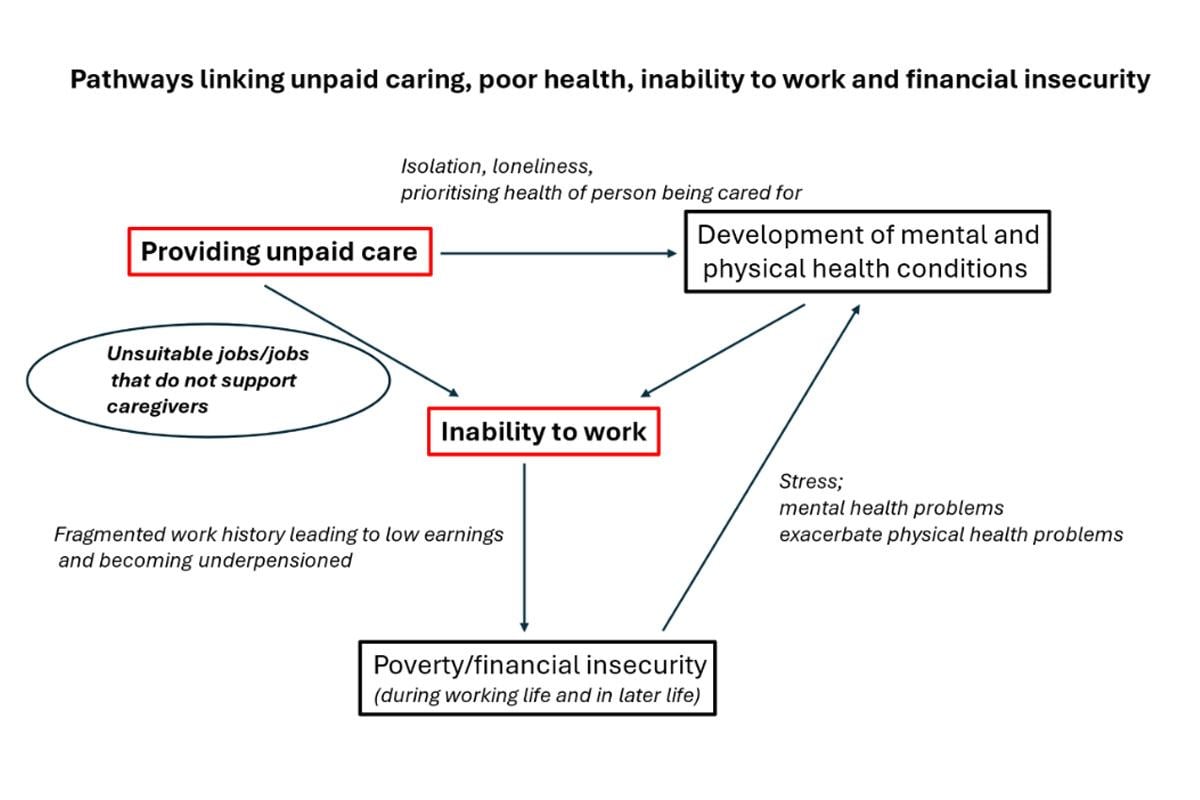

There is a clear and well-documented link between work, health and financial insecurity, but the evidence shows that unpaid caregiving is an important component of this framework.

Hence, supporting carers to combine their caring roles with paid employment will have an impact on their health and wellbeing and on levels of poverty in later life.

And caregivers want to combine caring and work: a survey of 50–64-year-olds found that being able to balance work with caring responsibilities would be an important consideration for them in choosing a new job.

Caring contributes to workplace inequalities

The patterns outlined here are not experienced equally across the population. This is because certain groups of people who are already disadvantaged in the workplace are disproportionately taking on unpaid caring roles for others. This includes people living in areas of deprivation, people with minority ethnic backgrounds and Disabled people.

For example, between the ages of 50 and 70, people living in the most deprived neighbourhoods are at least twice as likely to provide 35 or more hours of unpaid care per week as those in the least deprived neighbourhoods.

It is also striking that people living in more deprived areas become unpaid carers at younger ages than people living in less deprived areas. While caring in the least deprived 10% of neighbourhoods is largely concentrated between the ages of 50 and 69, in the most deprived 10% of areas it is more evenly spread throughout adulthood.

Moreover, the percentage of carers in the most deprived neighbourhoods providing the highest level of care (50 hours per week) is greater than that providing the lowest level of care (nine hours or less per week) at every age from 25 onwards. This has huge implications for the work histories, earning power, pension provision and financial security of the poorest carers.

I can't work because no employer is going to say, “Right, yeah, you can have next Wednesday and the following Monday and the Tuesday off because your mum needs appointments”..if they've got somebody who isn't caring for somebody, who can work regular hours, they're going to [employ them] over us.

There are also striking differences in levels of unpaid caring by ethnic background. Among women aged 50 to 64, Bangladeshi women (9.0%) are twice as likely, and Pakistani women (7.6%) 1.5 times as likely, to provide 50 or more hours of care per week as the population average (4.5%).

More than one in ten (11%) White Gypsy and Irish Traveller women aged 50 to 64 provide 50 or more hours of care per week – the highest rate of any ethnic group.

It’s possible that rates of caring among minority ethnic communities are even higher than the data shows because different cultural understandings of caring roles mean that people in some Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic communities who provide care don’t view themselves as carers.

There is also a difference among older Disabled people who are more likely than older non-Disabled people to provide unpaid care. Almost one in five (18%) Disabled people aged 50 to 64, and more than one in ten (12%) Disabled people aged 75 to 84, are carers (compared with 15% and 9%, respectively, among non-Disabled people). This means that Disabled people are disproportionately taking on unpaid caring roles for others.

Of note, these groups who are providing more unpaid care than the population average – that is Disabled people, people from deprived areas and from minority ethnic backgrounds – are already subject to workplace inequalities as a result of their disability and of discrimination and indirect, structural factors.

They also have worse levels of self-rated health and, like carers, in general, are under-pensioned. What we are seeing is the way in which multiple factors, including race, gender, disability and caregiving combine to amplify inequalities.

How to help those most disadvantaged by their caring role?

The link between caring and workplace inequalities with its knock-on effect on financial insecurity and poverty demonstrates the importance of supporting carers to stay in work.

Doing so can weaken the links with poor health and poverty and have profound implications for the quality of people’s later lives.

It requires workplaces to fully support flexible working and carers' leave so that carers can more seamlessly integrate their caring responsibilities with paid work.

Specifically, Ageing Better is calling on the next government to consult on the introduction of paid carer’s leave, extended unpaid carer’s leave, and a default right to flexible work from day one. This consultation should be an immediate priority after the General Election, with a view to enhancing these rights through new legislation by the end of the next Parliament.

Such a change would be particularly impactful for those carers who are already disadvantaged in the workplace and whose disadvantage is compounded by their caring responsibilities.

Supporting carers to work is vitally important for the outcomes of individual carers but it’s also important if we’re to maintain the system of unpaid care that our NHS and social care system relies upon.